Introduction

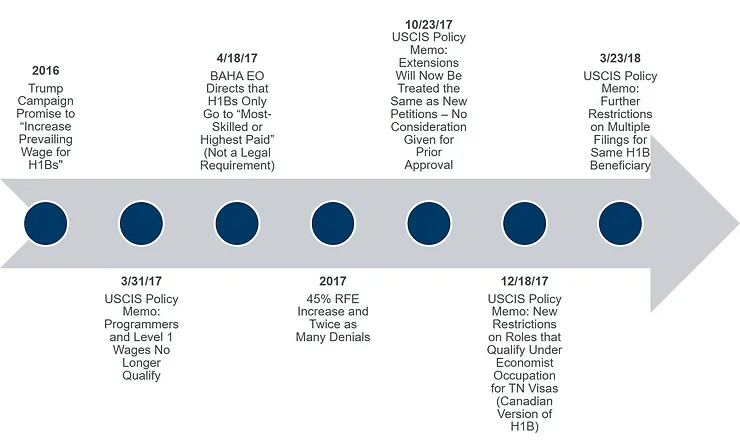

The H-1B work visa has been in the news a significant amount lately. It is the main work visa available to foreign professionals in the United States and tends to provoke strong reactions. As is the case in most countries around the world, some view it solely as taking away jobs from U.S. workers and therefore feel it should be further restricted, whereas others view it as a vital tool for U.S. businesses to tap into foreign talent to fill key roles that cannot be sourced locally. While President Trump has vacillated slightly from time to time, he appears to have been primarily in the first camp since his campaign. While he has not yet “fired” the H-1B visa (although at times it appears that he would like to do so if he could), his administration has been building a steady attack against it since shortly after he took office.

President Trump’s Position on H-1Bs from the Outset

“Increase prevailing wage for H-1Bs… will force companies to give these coveted entry-level jobs to the existing domestic pool of unemployed native and immigrant workers in the U.S., instead of flying in cheaper workers from overseas. This will improve the number of black, Hispanic and female workers in Silicon Valley who have been passed over in favor of the H-1B program.” [1]

This statement is typical of those made by individuals in the first camp mentioned above, who strongly promote adding further restrictions to the H-1B. It contains a considerable number of inaccuracies. Through breaking down and analyzing the statement and identifying these inaccuracies, it will help us to separate fact from fiction regarding the H-1B visa.

Separating Fact from Fiction

“Increase prevailing wage for H-1Bs”

The term “prevailing wage” is one of those confusing pieces of legal jargon. While some think it represents

the minimum wage that must be paid to an H-1B worker, prevailing wage actually indicates the “going rate,” or “market rate” for an industry occupation in a given location. The Department of Labor defines “prevailing wage” as “the average wage paid to similarly-employed workers in a specific occupation in the area of intended employment.”[2] The aim of this requirement is to prevent employers from sourcing foreign H-1B talent at below market wages instead of locally-based workers. Therefore, taken at face value, the plan to “increase prevailing wage for H-1Bs” is completely illogical because it would entail raising the market rate for all professionals working in the United States. This is what “prevailing wage for H-1Bs” is based upon and can only be increased if the total market salary rate rises.

Firstly, the H-1B regulations do not mention anything about entry-level positions. The requirement is that the role must be a “specialty occupation.”[3] A role is considered a specialty occupation if it meets one or more of the following criteria: (1) A baccalaureate or higher degree or equivalent is normally the minimum requirement for entry into the particular position; (2) Degree requirement is common in industry in parallel positions among similar organizations or the particular position is so complex or unique that a degree is required; (3) Employer normally requires a degree or equivalent; or (4) Nature of specific duties is so specialized and complex that knowledge required to perform the duties is usually associated with attainment of degree.[4] Essentially, it must be a professional role.

Secondly, and ironically, we have seen under the current Administration a sharp increase in immigration officers questioning H-1B eligibility for foreign nationals who are receiving entry-level wages. This directly contradicts this claim that H-1B visas are for entry-level jobs.

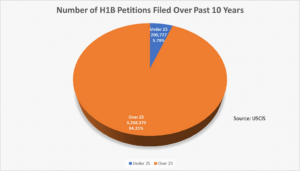

Lastly, only 5.79% of H-1B visas filed over the past 10 years were for foreign nationals 25 years of age or younger – ostensibly entry-level employees.[5]

“Flying in cheaper workers from overseas”

Firstly, U.S. employers are required by law to pay H-1B workers the actual wages paid to similarly situated

employees in the company, or the prevailing wage – whichever is greater.[6] It is therefore not possible for H-1B workers to be “cheaper.” Additionally, other employer requirements exist to help protect the U.S. work force from being undercut by H-1B workers. These include maintaining auditable paperwork, demonstrating how the actual wage and prevailing wage were calculated, and creating various attestations, including a statement from the employer to offer benefits to the H-1B workers on the same basis as U.S. workers.[7]

Secondly, the average compensation for an H-1B employee in 2017 was $93,497.[8] It is hard to characterize an individual earning nearly six figures as a “cheaper worker from overseas.”

Conclusion

As the above has shown, those in the anti-H-1B camp twist the facts to turn public sentiment against the H-1B work visa. The fact is that only 85,000 new H-1B visas may be issued each year (including the 20,000 allotted only to foreign nationals with U.S. Master’s Degrees). This represents a paltry .05% of the 160,597,000 total current labor force in the United States.[9] In addition, as mentioned above, there are a number of measures already in place to ensure that H-1B workers do not undercut the local workforce.

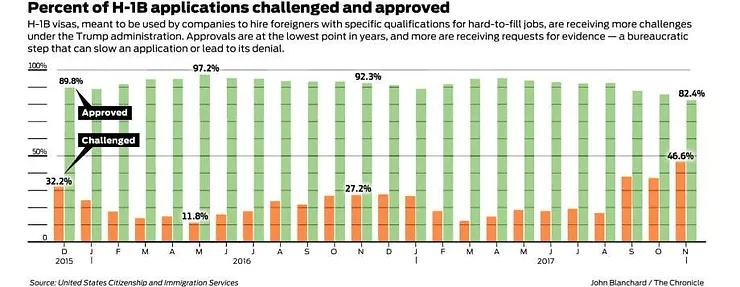

The end result is that we have seen twice as many H-1B denials in November 2017 compared to November 2016 according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Please follow Klug Law Firm PLLC on LinkedIn and Twitter to stay abreast of the latest updates in immigration law.

Endnotes

[1] https://www.donaldjtrump.com/positions/immigration-reform (no longer online).

[2] https://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/pwscreens.cfm (last visited January 31, 2018).

[3] Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (INA) § 101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b).

[4] 8 CFR §214.2(h)(4)(iii)(A),

[5]https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/Resources/Reports%20and%20Studies/Immigration%20Forms%20Data/BAHA/h-1b-2007-2017-trend-tables-12.19.17.pdf (last visited January 31, 2018).

[6] INA § 212(n).

[7] See http://webapps.dol.gov/elaws/elg/h1b.htm (last visited January 31, 2018).

[9] https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet?graph_name=LN_cpsbref1&request_action=wh (last visited January 31, 2018).